Tuesday May 20, 2008

Flawed wildlife law (Malaysia)

Stories by TAN CHENG LI

Our wildlife law calls for saving wildlife but it has limited powers to do so. TRAP a tiger and you will be arrested. Sell wine or plaster made from ground tiger bone and you can escape punishment, reason being, the Protection of Wildlife Act 1972 (PWA) is silent on “derivatives” of protected species.

That is just one of many flaws prevalent in the PWA. Here’s another: contrary to popular belief, the elephant is not totally protected but listed as a “big game animal” in the Act – which means it can be hunted if one obtains a hunting permit from the Wildlife and National Parks Department (Perhilitan).

And another: not a single plant, fish or amphibian is protected by the Act. There’s more: some highly endangered species are getting scant protection, legal hurdles abound when prosecuting offenders, penalties are ridiculously low ... the list goes on – no wonder our wildlife is depleting.

Is it ethical to trap an endangered species such as this leopard, just to stock a zoo or animal farm?

Many species owe their survival to the PWA but this legislation has not kept up with the times in some instances. Today, with wildlife being pushed to the brink by habitat loss, poaching and flourishing commercial trade, the Act is in sore need of an overhaul.

“In dealing with sophisticated wildlife criminals and their syndicates, this 35-year-old law appears to be failing to achieve what it set out to do in the 1970s.

It is outdated and there are many loopholes which unscrupulous criminals take advantage of, and at the expense of wildlife. We need the Act to be comprehensively reviewed, passed and implemented urgently,” says Malaysian Nature Society (MNS) executive director Dr Loh Chi Leong.

A review of the PWA dates back some 10 years and Natural Resources and Environment Ministry officials have said that a new Wildlife Protection and Conservation Bill is in the works.

However, this document remains tightly under wraps. Wildlife protection groups, despite their vast knowledge and experience in wildlife

management, are not privy to the Bill.

Nevertheless, MNS, Worldwide Fund for Nature, Wildlife Conservation Society and Traffic South-East Asia have come together to highlight crucial elements missing in the PWA. They first submitted their recommendations to the Ministry three years ago and again, last month.

Punishment and derivatives

Low penalties – under the PWA and meted out by the courts – is a worry for the non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Remember the case of the butchered tiger in Tumpat, Kelantan? The offender got off with only a RM7,000 fine in 2005 although the PWA allows a maximum of RM15,000.

That same year in Bentong, Pahang, a man caught with five bear paws, 32kg of bear meat and bones, one trophy barking deer head, four skinned civets, part of a hornbill beak, three skinned doves and nine live blue-crowned hanging parrots, was fined only RM5,500. Also in 2005, a man caught with four leopard cats in Gombak, Kuala Lumpur, and another with 294 pangolins in Perlis, were each fined RM3,000.

Wildlife laws have failed to keep up with growing threats to wildlife, such as the flourishing trade in wild meat.

Traffic regional director Azrina Abdullah says light sentences will not deter poachers. ”The impact of illegal trade on the survival of species underscores the need for strong penalties which reflect the harm caused,” she says.

The NGOs want penalties to be raised, to have a minimum, be based on the number of seized animals or wildlife products, and to include mandatory prison sentences for offences related to totally protected animals.

Another fault in the PWA is its silence over “derivatives”. It only states that “parts (readily recognisable)” of totally protected species cannot be traded. This oversight has hindered Perhilitan from stopping the sale of folk medicine containing by-products of animals such as the tiger and Sumatran rhinoceros.

And even when the product label states that parts or derivatives of a totally protected species form the ingredients, the burden of proof lies with the prosecution to show that the product does contain that stuff.

To close these loopholes, Azrina says the word “derivatives” should go into the PWA, together with a “claims to contain clause” as seen in Sabah and Sarawak legislations and the newly passed International Trade in Endangered Species Act 2007. There must also be legal provision to shift the burden of proof to the offender.

Listing of species

The PWA may have extensive lists of “totally protected” and “protected” species but these cover only terrestrial and marine mammals, birds and 40 species of butterflies. Glaringly absent are plants, amphibians, insects, spiders, freshwater turtles and tortoises, and fish. The result is oddities such as this: the polar bear is protected whereas the highly traded arowana fish is not.

The omission of plants from the PWA (because they are not considered “wildlife”) means that all our flora have no protection unless they grow in protected areas such as wildlife reserves and parks. The lists of protected species need a review as some species in trouble are still not totally protected, for instance the Asian elephant, Irrawaddy dolphin and pilot whale.

Freshwater turtles and tortoises are also getting a raw deal as they are under state control but not all states protect them.

Wildlife groups want all plants and amphibians added to the PWA, and the Asian elephant and sambar deer moved to the “totally protected” schedule. They say species listed under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species should be added to the PWA.

Except for marine mammals like whales and dolphins, marine species are ignored in the PWA. There was a debate over who should be in charge of marine species, Perhilitan or the Fisheries Department, with the latter eventually staking claim despite concerns that its priority is to improve fish hauls rather than conserving them.

The Fisheries Act 1985 had nothing on biodiversity protection until it was amended in 1999 and only then to include a handful of imperilled species such as the whale shark, giant clam and some marine turtles. Corals, other marine invertebrates, sharks and threatened reef fish such as the Napoleon wrasse and groupers remain unprotected.

The bigger picture

Listing animals for protection, however, serves little good if wild lands continue to shrink. Entire ecosystems and habitats, from lowland forests to wetlands, are now just as scarce as the wildlife they harbour and yet, the PWA does not oversee habitat protection and cannot stop conversion of wildlife refuges into plantations or settlements.

What is needed, says WWF policy co-ordinator Preetha Sankar, is legislation that is holistic in nature. To steer the PWA towards this direction, she says we need provisions that protect critical wildlife habitats, restore degraded habitats and provide for species recovery plans.

The public also deserves a bigger role in wildlife conservation. In Australia, the law allows the public to nominate species for protection. The PWA offers no such public involvement. To create an informed public which can help defend threatened wildlife, the NGOs propose an information register on these: all Perhilitan wildlife sanctuaries and their boundaries; regulations enacted under the PWA; issued licences and special permits and the quotas; prosecution cases; sites for licensed hunting and collection; and methods used to set hunting quotas and bag limits.

There is no denying that the PWA has helped safeguard Malaysian wildlife but in some areas, it is no longer current. One is hard-pressed to name a species that has rebounded thanks to the PWA.

It is time to fix the flaws with a new Bill that has bite, and soon, before more species tip over the edge.

NGOs have collected over 6,000 signatures calling for urgent and thorough review of the PWA. To sign the petition, go to www.mns.org.my.

Copyright © 1995-2008 Star Publications (M) Bhd

Dedicated to helping save orangutans and their forest homes.

Something to think about

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it's the only thing that ever has.

Margaret Mead

Margaret Mead

Abuse and humiliation of orangutans stopped?

Good news. From March 29 2010 the use of orangutans in circus-like shows in Malaysia has been officially banned. Let us know at once if you see anyone breaking this law....this animal park was caught doing so by Nature Alert.

SHAME ON MALAYSIA

The government owned Melaka Zoo forces this orangutan to take part in degrading and inhumane shows. Note the lack of hair on this orangutan's arms and lower body.

Information is power, when put to good use.

If you find what you see here to be interesting, do you think some of your friends might also like to know more about orangutans?

Please could you invite as many people as you can to visit this blog and subscribe to the news posts? As you can see and read, orangutans need all the help they can get.

Many thanks.

Nature Alert

Please could you invite as many people as you can to visit this blog and subscribe to the news posts? As you can see and read, orangutans need all the help they can get.

Many thanks.

Nature Alert

Nine years secured to a three metre chain. Imagine if you will.

"Mely" enjoying fruit supplied by COP and Nature Alert.

Waiting to be rescued

Under lock and chain for at least nine years.

How governments do deals which wreck environments, people and countries

Highly Recommended reading and available from Amazon

Chained up day and night.

But confiscated and rescued by COP in January 2010.

COP to the rescue

The final moments before being released forever from the heavy chain around its neck.

A helping hand

After maybe nine years of being confined to a wooden crate this orangutan is now on the way to a rescue centre and one day back to the forest.

SOMETHING TO THINK ABOUT

What changes the world for the better is the passion of certain individuals, not governments, not big organisations.

Paul Watson

Sea Shepherd

Highly Recommended Book

Available from Amazon and by far the best book ever written on orangutan conservation.

Hall of Shame for President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono and the Palm Oil Industry.

Nothing can prepare one for the sight of the systematic extermination of orangutans by the government of Indonesia.

Look at the photos and news articles on these pages in the context of a statement the President made to the media on 10th December 2007.

“In the last 35 years about 50,000 orangutans are estimated to have been lost as their habitats shrank. If this continues, this majestic creature will likely face extinction by 2050,” President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono said at the launch of an orangutan conservation plan at the climate talks in Bali.

“The fate of the orangutan is a subject that goes to the heart of sustainable forests … To save the orangutan we have to save the forest.”

Statements like these are most welcome, but unless backed up by action, such words fall on deaf ears within the Ministry of Forestry....who are busy granting licences to cut down the very forests the President says they should protect!

Look at the photos and news articles on these pages in the context of a statement the President made to the media on 10th December 2007.

“In the last 35 years about 50,000 orangutans are estimated to have been lost as their habitats shrank. If this continues, this majestic creature will likely face extinction by 2050,” President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono said at the launch of an orangutan conservation plan at the climate talks in Bali.

“The fate of the orangutan is a subject that goes to the heart of sustainable forests … To save the orangutan we have to save the forest.”

Statements like these are most welcome, but unless backed up by action, such words fall on deaf ears within the Ministry of Forestry....who are busy granting licences to cut down the very forests the President says they should protect!

Another palm oil victim - one of tens of thousands - so far.

For a close up of this brutally treated orangutan, please see below.

Mother shot and eaten. Baby beaten and tied to a pole.

The plight of a baby orangutan rescued from a palm oil plantation workers in Borneo has exposed the high price these endangered primates are paying for the production of palm oil. The 2-3 year old female was found hogtied to a pole and had clearly been brutally beaten. Covered in cuts and bruises, she was also severely dehydrated and emaciated after being starved for days or even weeks.

Palm oil kills - no doubt about it.

Villagers protest against palm oil companies.

Tropical forest, home to orangutans etc.

Threatened by palm oil companies.

Saved by COP

Mother murdered by palm oil company

Tortured by palm oil company employees

Rescued and treated by COP, this orangutan has since been released back into a forest.

Palm oil plantation victim

Orphaned by a palm oil company with help from the government of Indonesia.

Indonesia's Alcatraz for orangutans

A living hell for this orangutan.

Guilty of being an orangutan

A prisoner held by the Indonesian government

Shame on the Ministry of Forestry

A life behind bars. Why?

Day after day, 24/7 ..........

A magnificent male orangutan facing life imprisonment behind bars.

Kept prisoner in filth and squalor

Things just go from bad to worse

Solitary confinement .

There can be no excuse for treating an orangutan like this.

Welcome to Indonesia

Where orangutans are incarcerated by the government.

No hope?

Has this orangutan lost the will to live?

Shame on Minister Kaban

Young orangutan in a 1.5 sq. metre cage 24 hours a day and tormented by zoo visitors.

What future do you think this orangutan has?

How much longer can the Indonesian government carry on abusing and killing orangutans?

Born in the wild.

Life behind bars - where the government of Indonesia prefers to see its orangutans.

Dying for help

With their mothers slaughtered these baby orangutans face a life of torment, torture and hunger, thanks to the government of Indonesia.

Torture chambers for orangutans at an Indonesian zoo

These orangutans have been kept like this for nine months. Until Nature Alert and COP protested the cages were left outside in all weathers.

Solitary confinement courtesy of Indonesian zoo

Caged like this 24/7 for nine months, with no end in sight.

When you think you are to busy to help, please could you reflect for a moment on .........

The following extract refers to environmental problems in general. I just hope you find it as thought provoking and relevant to orangutans as I have.

"This is such a shocking and unpalatable fact that most people deny it, or they just don't want to think about it. They believe as individuals, they can do little about it, so push it to the back of their minds. But I can't do that.

When something has to be done, we need to do it. It doesn't matter how big the challenge is or how hard the solution; if I know something is wrong, and I am in a position to help, I will do my best to make it right." Duncan Bannatyne, successful British businessman.

Formerly home to orangutans and other wildlife.

Part of the price we all pay for palm oil.

Can you see the rainforest?

No? That's the way the palm oil companies like to see things.

Begging for food - not for fun.

Reduced to begging for food, this orangutan (one of two) is in a unofficial zoo in West Kalimantan. Their enclosure has nothing but bare earth, no protection from a blisteringly hot sun, a concrete tube to shelter/sleep in and no fresh water to drink.

Bored and hungry - for as long as this orangutans lives

Born to be free. Imprisioned for life.

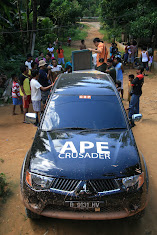

The COP Rapid Response Team

Their arrival in a remote village often generates a lot of interest. Please see July 2008 Blog page for more details..

Saved by COP

Please see July 2008 Blog page for more details.

Mother killed and her baby tied up like this for six months.

We found her at the home of a family who had bought her from her mothers killer. Please see photo immediately below - she is now safe, rescued by COP with the local Forestry Police.

Safe and sound - now

Saved by The Centre for Orangutan Protection and its sponsors/supporters.

Another palm oil victim

Rescued by COP and The Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation

With its mother killed this orangutan's new owner keeps it chained up.

A baby orangutan with nowhere to go. A mother's love replaced with a chain.

How very, very sad.

What hope is there for this orangutan?

In this small crate there really is an orangutan.

Torture takes many different forms when it comes to dealing with orangutans.

Alone and abused.

Yes. There is an orangutan in this cage.

Chained to, rather than living in a tree.

There's no escape.

At a West Borneo amusement park.

Look at the rubbish this orangutan has to live with.

Escape is not an option.

same as picture below.

Yet another victim of logging and/or palm oil.

Alone, malnourished and very sad in a transit centre.

Palm oil companies take everything.

Imagine; this was once a rainforest.

Life imprisonment

Five adult orangutans are crammed into this dark, featureless cage in a zoo. All five began life in the wild.

Orphaned by loggers or palm oil companies - often the same thing.

Missing its mother. Look at her eyes and you have to wonder what she is thinking don't you? STOP PRESS this baby has since died.

A little light refreshment goes a long way.

Water melon was always a firm favourite of the orangutans. In all the differnt locations we never once saw fresh drinking water provided.

A Tasty treat

Everywhere we went we took lots of different fresh fruit to give to the hungry orangutans we always discovered in various locations.

Same location as above.

We provided food and some small branches, and they loved both.

Again, the same location

We hope we made him a little happier than he appears. The lives of these two orangutans must be almost unbearable. We hope to arrange their transfer to a rescue centre soon.

West Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo)

Two young orangutans kept at an amusement park. They were wild born. Mothers killed by loggers.

Rescued last year and now at a rehab. centre with an uncertain future.

This baby saw her mother being killed and eaten.

Lawbreakers

Illegal loggers

The torture of orangutans is seemingly never ending.

With its left arm chained and padlocked to its neck, this orangutan is literally being tortured at an amusement park in West Kalimantan (Borneo)

Awaiting rescue from what was once its home.

With nowhere left to run, this tranquillized orangutan was rescued and moved to another forest.

Apocalypse now - Indonesian style with help from Malaysian companies.

Rescuers looking for orangutans made homeless by a palm oil company. Virgin rainforest recently stood where there is nothing but a few small trees remaining, which by now will also have been cleared away. Nov. 2007

Yet another palm oil victim

-a.jpg)

With its mother killed, this baby with an injured eye was caged by workers until rescued by WWF Indonesia.

Illegal loggers in action. October 2007

Access to log these trees illegally was gained via a palm oil plantation road. This forest is home to 50 orangutans and palm oil companies want to log it.

The road to ruin - Indonesia style.

Where once stood a magnificent rainforest full of wildlife.

Mother and baby orangutan.

Oil palm companies have killed thousands like these two.

Palm oil victim. Mother killed.

This baby will have seen its mother slain.

Nothing, absolutely nothing, left of the forest, except for its soil.

It's all about money, greed and corruption.

Destruction and desolation as far as the eye can see

So much for Borneo's rainforests - look what palm oil companies have done to them.

They can barely cut down and remove the trees quick enough for their liking.

Palm oil companies destroy rainforests.

Freshly cut trees

These trees could end up as garden furniture in your local store.

Not a tree in sight - courtesy of oil palm companies.

Oil palm plants growing where rainforest once stood.

Web site to check out

How and where to watch orangutans

About Me

Blog Archive

-

▼

2008

(781)

-

▼

May

(105)

- Sime Darby`s investment in Indonesia reaches US$1....

- Australia gives $4.5m for foreign forests

- Response from Unilever

- Major forest fires in sight as more hotspots detected

- Illegal logging trade forces jungle brothel in Ind...

- Clean hair or clean air?

- UNILEVER COMMITS TO CERTIFIED SUSTAINABLE PALM OIL

- Indonesia's Astra Agro Plans to Boost Palm Oil Output

- Chainsaw threat to great apes

- Orangutans' foster mother ecourages her brood to g...

- Malaysian palm oil conference focuses on sustainab...

- BKSDA officials named suspect in Riau forest funds...

- BKSDA officials named suspect in Riau forest funds...

- EC-RI FLEGT project takes journalists to Danau Sen...

- The abuse goes on and on, and on .....

- Orangutan making money for media companies

- North Sumatra again blanketed in haze

- Govt plans estate for downstream palm oil industry

- SE Sulawesi agency seizes illegal timber from 3 ships

- The Indonesian Government plans to increase its pa...

- Indonesia considering mandatory use of biofuel

- Greepeace encourages sustainable growth of palm oi...

- Tortured displays

- First Lady and Forestry Minister honoured for tre...

- Tortured displays

- Illegal Logging Eradication: Supreme Court Termina...

- Orangutans fight for their survival on a protected...

- Certified Non-Rain Forest Palm Oil Set For Germany

- Massive media coverage of the palm oil industry wi...

- Recent video film.

- Medco invests around US$1 bln to diversify business

- North Sumatra`s Walhi reports forest conversion to...

- Company exec acquitted of illegal logging charges ...

- RI opts for carbon trading over halting deforestation

- United Tractors plans to spend $170 million on coa...

- Seized logs abandoned

- First Lady, forestry minister honored for tree pla...

- Stars support graft fight

- Tropical deforestation is 'one of the worst crises...

- Wildlife populations 'plummeting'

- Riau to invite foreign investment in plantation, f...

- Govt eyes wood products certification body

- Bakrie to expand oil palm plantation area

- Charles urges forest logging halt

- Sainsbury's first with sustainable palm oil

- Unilever takes the lead to stop deforestation in I...

- United Plantations Q1 earnings up 194%

- New Britain doubles profit from palm oil

- Indonesian forests to be more than just carbon sinks

- International Paper Threatens to Violate Own Polic...

- Joint move against log thieves

- KPK in Riau for inquiry audit

- Police back Tempo in logging libel suit

- National Geographic

- Govt urged to review forest concessions in Riau

- Indonesian Warship Captures Boat Carrying Illegal ...

- Lawmaker Grilled in Forest Graft Case

- Indonesia Losing US$16 bln Per Year By Natural Res...

- KPK, Riau Police Cooperate To Tackle Illegal Loggi...

- Riau Police Chief Replaced, KPK to Probe Illegal L...

- Indonesia Adopts Stringent "Green" Palm Oil Standard

- Malaysia Will Not Protect Officials Involved in Il...

- KPK forestry inquiry heats up

- Singapore's Wilmar Q1 net profit jumps 7 times

- Palm oil firms vow to stop using forests

- PROTECTED AREAS USED TO EXPAND INDONESIAN OIL PALM...

- Forest conversions stand: Ka'ban

- MALAYSIA'S SITT TATT IN JV TO BUILD PALM OIL MILLS...

- PALM OIL DRIVES ORANG-UTAN TO EXTINCTION

- A Helping Hand

- Centre for Orangutan Protection - in Action

- Orangutan rescue

- Riau regent accused of stealing Rp 1.2t

- Businessmen admits paying Batam authorities to use...

- Lawmaker grilled in forest graft case

- RI forest conversions alarming: Greenomics

- Conservationists say Indonesian orangutans face ex...

- Speaker : Malaysia not to protect officials involv...

- Police detain Greenpeace activists dressed as oran...

- Conservationists say Indonesian orangutans face ra...

- Palm oil wiping out key orangutan habitat: activists

- Orangutan habitat in peril due to palm oil plantat...

- Orangutan endangered in Indonesia

- Indonesia adopts stringent "green" palm oil standard

- Neste filling station closed by anti-palm oil demo...

- Ministry, USAID team up for conservation project

- Khir: No logging on my watch

- We did not approve logging in forest reserve, says...

- ILLEGAL LOGGING MAY CAUSE FARMERS TO LOSE PADI CROP

- Orangutans in danger of dying out

- RI forest conversions alarming: Greenomics

- Big Plans for Biodiesel Stall in Southeast Asia

- Foster forest concept, community-based reforestation

- Forest Crimes: Political will is needed

- China farms the world to feed a ravenous economy

- Police recover more logs in Riau; foil smuggling i...

- Illegal loggers push anti-graft police chief shuffle

- Unilever palm oil policy wins fans

- Crackdown on traffickers strains Thailand's wildli...

- Crackdown on traffickers strains Thailand's wildli...

-

▼

May

(105)

Recommended Viewing and Reading

- Guidebook to the Gung Leuser National Park

- Book: The Lizard King

- BOOK: Confessions of an Economic Hit Man